Jaidyn Probst with a portrait of Rant-che-wai-me (Female Flying Pigeon), Iowa. 82-51-10/57030

Jaidyn Probst with a portrait of Rant-che-wai-me (Female Flying Pigeon), Iowa. 82-51-10/57030

A guest blog post from Jaidyn Probst, a second year Harvard student and member of the Lower Sioux Indian community. Jaidyn is a concentrator in Cognitive Neuroscience and Evolutionary Psychology who worked with the Peabody remotely this past January break as a “wintern.” The Arts & Museums winternship program, run by the Harvard Office of Career Services, offers students a chance to learn more about what it’s like to work in a cultural institution.

The Peabody Museum’s collection includes twenty-six 19th-century oil paintings by Henry Inman (1801-1846). These portraits depict Native American delegates. Inman was chosen by the then Superintendent of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Thomas McKenney, to copy the original collection of paintings by Charles Bird King (1785-1862). The history of the paintings is something that I learned a bit about while taking a freshman seminar in 2019 with Professor Shawon Kinew. Working as a “wintern” for the month of January, I realized I wanted to dive deeper into the paintings, specifically to learn about their existence at the Peabody. I was able to speak with Meredith Vasta, Collections Steward, and Cristina Morilla, Special Projects Conservator, about their work with the collection.

Regarding the collection, I learned that the composition of the paintings is something that has been stirring up conversation. Meredith and Cristina took time to talk with me about how the stereotypes of the paintings have been in discussion lately and showed me a presentation they had put together delving into this issue

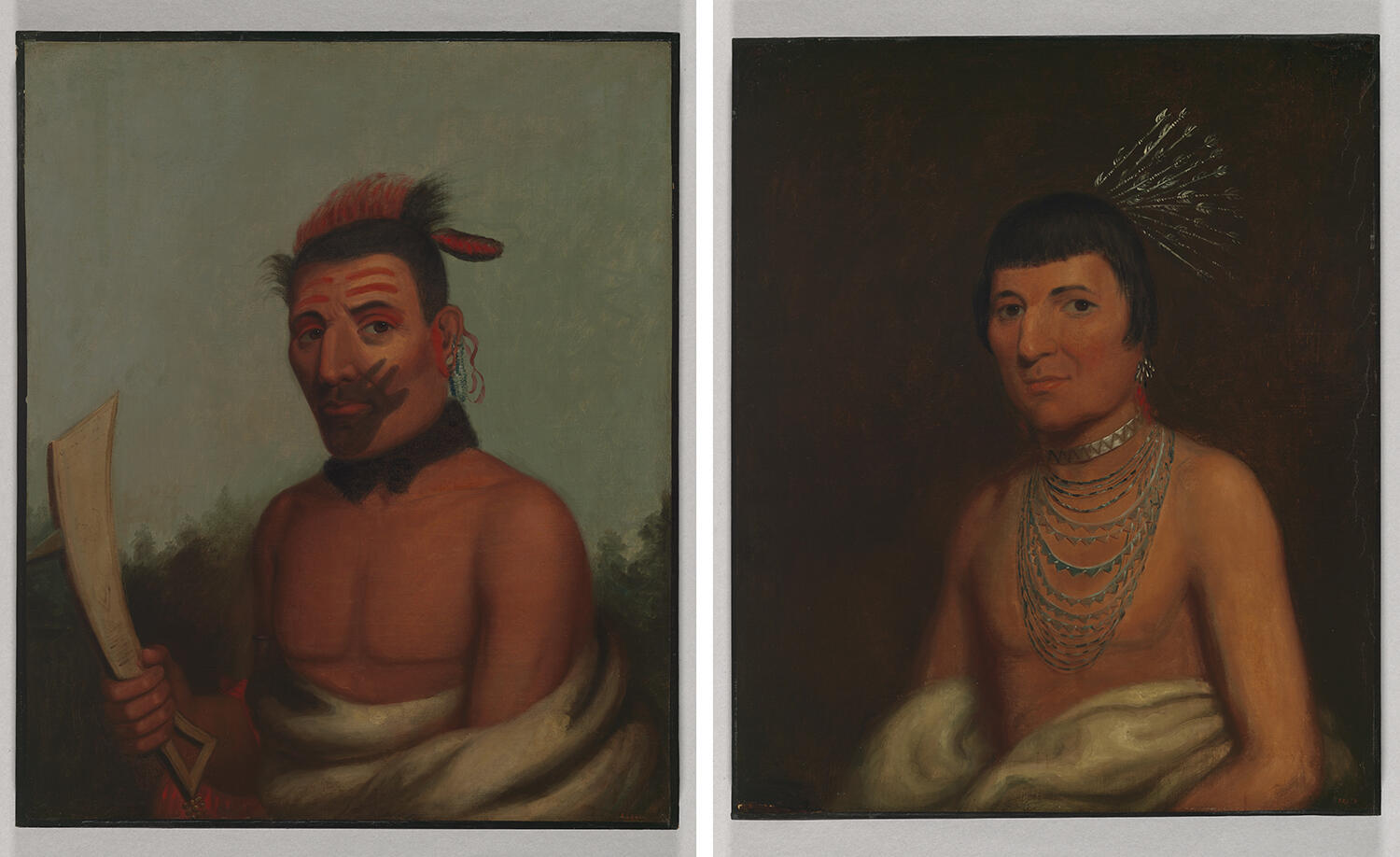

Historically, the skin color of sitters within portraits has been divided by gender, social class, and race. Native American portraits typically have less complex palettes in terms of skin color. This relates to literature of the time where racial issues were endorsed by scientific studies. Cristina shared with me that the x-rays of the Inman paintings reveal less white pigment in the flesh and more reds and ochres instead.

It is questioned whether Inman enhanced the redness of the skin to portray the sitter as non-white, or as a way to “other” the sitter. This is an important conversation in modern society, as Native Americans are continuously winning the fight against racist representations of our people as mascots and brand faces. Cristina explained that, from her level of expertise, she believes the stereotype of a redder skin tone was built on purpose by Inman, based on the layers of the pigments and results from technical analysis. Something else to consider is that a few of the Inman paintings depict the sitter wearing red pigments on their face, which is visibly contrasted against the skin tone. The color red often has significant cultural meanings which varies across tribes and communities.

Left, Harvard Art Museum conservation fellow Julie Wertz uses x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy to conduct a non-invasive analysis of the pigments used in the painting of an Ojibwa chief whose name is currently unknown 82-51-10/28266. Right, Cristina Morilla removes varnish from the portrait of Ojibwa chief Kit-chee-waa-be-shas (The Good Martin) 82-51-10/28285.

Left, Harvard Art Museum conservation fellow Julie Wertz uses x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy to conduct a non-invasive analysis of the pigments used in the painting of an Ojibwa chief whose name is currently unknown 82-51-10/28266. Right, Cristina Morilla removes varnish from the portrait of Ojibwa chief Kit-chee-waa-be-shas (The Good Martin) 82-51-10/28285.

One final piece of interesting information I was able to learn from Meredith and Cristina concerning this collection was that a conservator in the 1930s put a red varnish over the paintings, which would not have happened had the sitter been white. Overall, this experience was very educational and I thank Meredith and Cristina for meeting with me and talking about their work!

Author: Jaidyn Probst