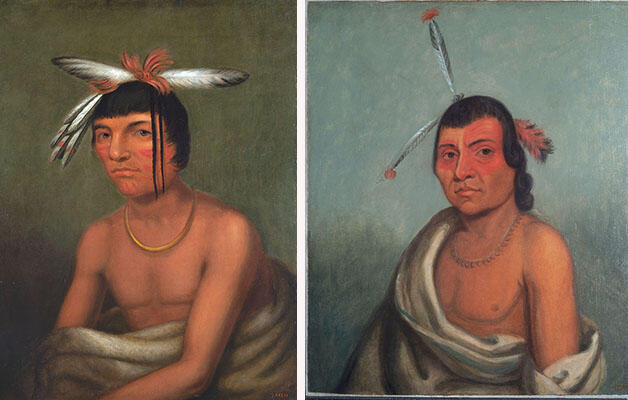

Fig. 1. Portraits of Mish-Sha-Quat (Clear Sky), and Pe-a-jick, Chippewa. Gift of the Heirs of E. P. Tilestown and Amor Hollinsworth, 82-51-10/28256 and 82-51-10/28277.

One of the highlights of the Peabody Museum’s painting collection is a series of portraits representing Native American leaders who travelled to Washington DC in the early 19th century. They were painted by Henry Inman (1801-1846) copying originals from Charles Bird King (1785-1862). Most of King’s originals were lost in 1865 fire that destroyed the old Smithsonian castle. In 2018 the Museum started a collaboration with the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at Harvard Art Museums to address the conservation and research of this collection.

Who is represented and why?

Delegates from the Ojibwa, Iowa, Winnebago, Sauk, Wichita, Menominee, Creek and Ottawa tribes were portrayed during their travels to Washington DC. They met Presidents and members of Congress to advocate for the preservation of their homelands and communities during this turbulent era of warfare, removal of and land loss by Native Nations. Some of the sitters were painted wearing medals of “Peace and Friendship” that might have accompanied a treaty or a deal with native tribes.

Fig. 2. Portrait of an unknown Ojibwa man wearing a medal with the image of Thomas Jefferson. 82-51-10/28274

These portraits served as models for the lithography that illustrated the publication The History of the Indian Tribes of North America a three-volume enterprise that became one of the most important anthropological initiatives of the century. Most of the oil portraits have a lithographic version in the publication.

The Conservation Project

Fig. 3. Conservator Cristina Morilla during the retouching process of one of the portraits.

The current conservation project is to stabilize, clean and improve the appearance of the portraits, which have a complex history of previous interventions.

The institutional collaboration between the Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology and the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies includes not only conservation and material research, but also historical and curatorial investigation. We aim to better understand the history of Native American portraiture in the first half of the 19th century, while preserving the memory of the individuals portrayed and the cultures that they represent.

Scientific and material studies

e scientific examination of the portraits provides an insight

Fig. 4. Conservator Kate Smith (Straus Center for Conservation, Harvard Art Museums) examines one of the portraits by Infrared photography.

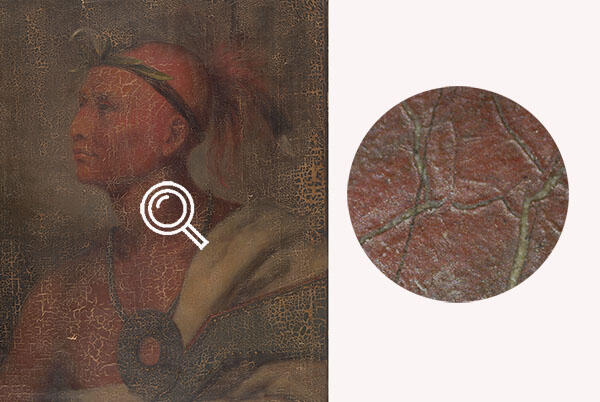

The materiality of the portraits is analyzed with X-radiography, infrared photography and paint sampling to understand the preparatory underdrawings, the structure of the paint layers, and the use of driers and varnishes. The generation of artists working at this time engaged with considerable exploration of new materials. Painters sometimes fabricated their own paints, experimenting with pigments and binders. This practice might have impacted the aging process of the paints and the paintings. Fig 5 shows an example of drying cracks a stable, but disfiguring effect which would have occurred as the painting dried, soon after its completion. These types of cracks are associated with experimental materials added to the paint to speed drying or achieve particular texture, with unfortunate results.

Fig. 5. Detail of the paint cracking on the portrait of Tah(sha)-col-o-quoit. Sauk. 82-51-10/28241

The information gathered from the different analytical techniques is then interpreted by an interdisciplinary group of conservators, scientists and curators that come to an agreement for the treatment to be done.

Fig. 6. Scientist Julie Wertz examines and analyzes the portrait of an anonymous Ojibwa man with a portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometer.

What can we learn?

The conservation of the paintings facilitates a conversation with the communities that are represented, making the portraits accessible for study and consideration. Shawon Kinew, assistant professor of history of art and architecture and Shutzer Assistant Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, led a course about the portraits in 2019 and reflected on how the collection enables “a conversation with the past” acquainting students with a part of U.S. history that is often overlooked. “The takeaway is that the past still needs to be interpreted in many ways,” says Kinew, “But also, that the people who are represented in these paintings didn’t become extinct. Their descendants are still here, and their nations are still here. Their languages are still spoken; the things they’re wearing are still worn and used in ceremony today. There’s something very powerful about the paintings and the sitters because they transcend what was once described as a moribund history”.

Jaydin Probst, third year Harvard student and member of the Lower Sioux Indian Community, examined the portraits with us and reflected on the significance of Native American representations. Her reflections offer a invaluable and indispensable point of view on the Inman collection.

Acknowledgements

This project is possible thanks to collaboration between the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology and the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at Harvard Art Museums. Special thanks to Kara Schneiderman (Director of Collections at Peabody Museum), T. Rose Holdcraft (Senior Conservator, Peabody Museum), Meredith Vasta (Collections Steward), and the generous collaboration of Narayan Khandekar (Director of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies and Senior Conservation Scientist) and the expertise and altruism of Kate Smith (Head of Paintings Lab at the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies).